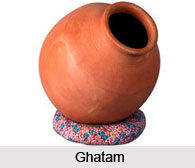

Originating from the southern regions of India, the Ghatam is a traditional clay percussion instrument deeply rooted in Indian classical music. Its significance lies not only in its distinct sound but also in its cultural heritage and historical significance. In this article, we will explore the types, significance, and various uses of the Ghatam in Indian music.

Significance:

The Ghatam holds a prominent position in Indian classical music ensembles, particularly in the Carnatic tradition. Its unique construction from clay gives it a resonant, earthy tone that adds depth and texture to musical compositions. Historically, the Ghatam has been used in religious ceremonies, folk music, and classical performances, symbolizing the rich cultural tapestry of India.

Types:

While the basic construction of the Ghatam remains consistent across variations, there are subtle differences in size, shape, and playing technique. The two main types of Ghatam are the "Mud Ghatam" and the "Metal Ghatam." The Mud Ghatam is crafted entirely from clay, shaped by hand, and sun-dried before being baked in a kiln. On the other hand, the Metal Ghatam is made from brass or copper and offers a different tonal quality compared to its clay counterpart. Additionally, variations in size and weight produce different pitches and volumes, allowing for versatility in musical compositions.

Uses in Indian Music:

The Ghatam serves multiple purposes in Indian music as a percussion instrument, contributing rhythm, melody, and texture to performances. In classical concerts, it often plays a foundational role as part of the percussion ensemble, providing the rhythmic framework for compositions. Skilled Ghatam players demonstrate intricate patterns and improvisations, enhancing the dynamics of the music and engaging the audience.

In addition to classical music, the Ghatam is also utilized in folk and devotional genres, where its rustic sound adds authenticity and emotional resonance to the music. Its versatility allows it to adapt to various musical styles and contexts, making it a versatile instrument in the hands of adept musicians.

Furthermore, the Ghatam is often featured in solo performances, where its expressive capabilities are showcased to full effect. Solo Ghatam recitals demonstrate the instrument's rich tonal palette, rhythmic complexity, and dynamic range, captivating audiences with its virtuosity and mastery.

The Ghatam stands as a symbol of India's musical heritage

and cultural diversity. Its significance extends beyond its role as a mere

instrument, embodying centuries of tradition and craftsmanship. Whether in

classical ensembles, folk gatherings, or solo performances, the Ghatam

continues to enchant listeners with its earthy timbre and rhythmic vitality,

ensuring its enduring presence in the tapestry of Indian music.